Clothing in Semlac is perhaps the hardest detail to keep track of in Between Worlds. I have photos, but they don’t match the exact years that Between Worlds takes place in. Fashion in between the wars did begin to modernize, but to what extent I don’t fully know. In this blog post, I’ll take you through what I do and don’t know about how Elisabeth would’ve dressed.

My Own Preconceptions

It’s important to start here. I’ve always enjoyed looking through old photos, and there was certainly no shortage of them from both sides of the family. In fact, given what little they could bring with them when they left Europe in the 50s, I’m surprised at how many photos made it across the Atlantic.

For example, every photo I’ve ever seen showed women’s and girls’ hair either covered or pulled back. I read about Elisabeth’s most likely hairstyle with this information in mind. Unfortunately, I let it colour how I interpreted descriptions of farmers’ clothing at that time.

Adding to my assumption that girls wore the hair up was a photo from Liebling, one of the feeder towns to Semlac. It’s likely from the 50s or 60s, but it shows girls with their braid pinned on top of their head.

Although it took me a year to realize it, I was partially wrong with Elisabeth’s hairstyle: Instead of the two braids along the sides of her head forming into a braid that got pinned on top of her head, Elisabeth would have most likely left her braid down. In addition, she would have woven a thick ribbon through the single braid and then tied it into a bow at the bottom. I’m sure it was absolutely lovely.

The Role of Religion

There were two main German groups in Semlac: the Lutherans and the Calvinists. I understand there were a few Catholics, but they came from across the river. One Catholic family owned a shop, for example.

However, most Germans in this region were Catholics. Although their general dress code was the same—colourful clothing and generally uncovered hair for girls, colour and covered hair for married women, and black or navy clothing and covered hair for older women—there were differences.

For example, look at the following photos of the headscarves. I honestly don’t even know if I’d call the one a headscarf. The Catholic one is much more ornate, and many of the photos you’ll see of Danube Swabians (the ethnic group Elisabeth’s people are categorized into), you’ll see some very elaborate head coverings for women. Lutherans, by contrast, wore more humble head coverings.

Notice the folds and embroidery on the headscarf. This is from a Catholic village.

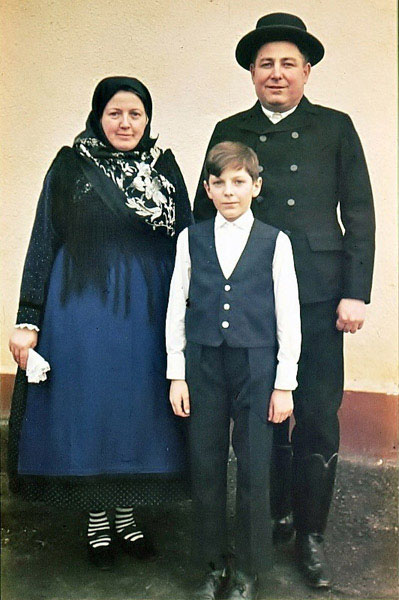

Although clearly taken decades after Between Worlds, this photo shows what Mammi, Tata, and perhaps little Luki would have worn to church.

The Schöndorf tracht in colour. Photo likely from the 1950s.

Elisabeth’s Clothes: Blouses

Some old photos make it look like the women wore dresses in Semlac. They generally didn’t, though girls did. When this transition happened, I’m not sure. Instead, women wore a skirt + blouse + full apron. The blouses were hand-decorated and could have lots of notions and stitching.

The other piece of clothing worn on top was the tschurak, a somewhat tight-fitting, light jacket that extended just past the hips. It was part of the traditional dress earlier on but, according to my book on Semlac, was eventually replaced by the blouse as just described.

The following photo is from 1917. The woman seated is Elisabeta Stefan, the inspiration for Elisabeth’s name, and standing next to her is her daughter, Katharina Wolf (not the Katharina Wolf who inspired the character of Elisabeth). Notice the crisp folds in Elisabeta’s apron.

Elisabeth’s Clothes: Skirts

My maternal grandmother had trained in her youth to become a seamstress and sew the traditional dress clothing. She was born in 1920, so she is the generation after Elisabeth. In addition, her village of Germans was Catholic. However, it suggests to me that her village assumed that life would follow its traditional path, with perhaps a few changes as they arose. World War II changed all of that, but that’s for another series of books.

In Semlac, the coveted style of skirt for women was made of cashmere and ideally dyed blue-green. I did my best to look for photos online, but alas, despite what we all believe, Google still hasn’t found everything. However, I do have this photo of Katharina Wolf, the inspiration for Elisabeth. It was likely taken during World War I. Notice how her bangs are short, but her hair is pulled back.

Elisabeth’s Clothes: Footwear and Socks

Exactly what their shoes look like has been perhaps the most difficult aspect of describing the clothing in Semlac. In the book I use to help me describe and learn what Elisabeth, her family, and her friends would have worn, it says that women usually wore leather slippers during the week and satin slippers for their Sunday dress. Girls wore what appear to be ankle-high boots made of black leather with laces.

Heels and buckles apparently did not enter the village until the 40s; however, the book does have a picture of girls in the 1930s wearing white shoes with buckles and heels.

Socks for girls until around this time (and likely a little later, depending on the family) were hand-knit. In the winter, women knit socks from wool and in the summer from cotton. They had horizontal stripes: blue-black or green-black in the winter, and white-black or white-blue in the summer.

The more I learn, the more I wonder what differences were truly age-related. For example, the book says that confirmed girls wore socks that were striped either white-black or white-blue. I can’t imagine that they would’ve stopped wearing those warm winter socks if they still fit.

Another reason why it’s hard to nail down exactly what Elisabeth wore.

Economic Status

Economic status also affected clothing in Semlac. The book about Semlac says that the wardrobe and style of dress described in its pages are specific to farmers. Rich people dressed differently. Hair length was the single example I found that illustrated the difference: women who belonged to the higher strata in the village may have cut their hair short by this time. But that’s all I’ve learned so far. With Georg being a blacksmith, his wife, Eva, could very well cut her hair. We’ll see!

However, research I had carried out for me in Eastern Europe suggests that class distinction was also somewhat related to ethnicity. Although my researcher couldn’t find specific data, he extrapolated from directories by last name the likely ethnicity of various workers. This may sound like a prejudiced way to approach this problem, but remember that ethnic boundaries we’re much clearer in Elisabeth’s times.

The one misleading factor in this approach, though, is that some Germans took on the Hungarian equivalent of their name somewhere in the family’s history. This happened often in the Calvinist church in Semlac. So it is possible that someone with a Hungarian last name was actually German. Without specific census data, though, I can only work from assumptions.

Besides, the most important thing to know is how the farmers dressed.

Writing Historical Fiction

One beauty about historical fiction is reliving what life may have been like in a different time and place. I am sorry that I can’t recreate Elisabeth’s dress customs exactly. But I hope the important aspects are clear: She never wore pants (inconvenient, from my point of view) and had to wear her hair in a prescribed way.

On the other hand, her clothing showcased the handiwork crafted by the women in her family and broader circle of friends. That’s certainly something we’ve lost that would be beautiful again, isn’t it?